A woman walks into a therapist’s office, dragging her teenage son. “Doctor,” she says. “Please help! My son thinks he’s a chicken.”

The son says: “If there is one thing I can tell you about chickens, it’s that we know who we are.”

“Where is your proof?” the woman demands of her son. “You have no feathers.”

“True,” the son replies. “I went through the wrong puberty.”

The woman turns to the therapist: “You see what I mean? He’s lost his mind!”

The therapist replies: “You’re the one arguing with a chicken.”[1]

The above is an excerpt from Irreversible Damage by Abigail Shrier

Had you told yourself twenty, or even ten, years ago what politics around race and sex would look like in the early 2020s, how much of it would be believable? Elite culture today demands submission on the part of the white racial majority,[2] failing to affirm gender dysphoria in children is a fireable offense,[3] intersectionality has encroached into workplaces,[4] and in elite and legacy media the conversations on disparities that exist between groups has been severely circumscribed to the singular factor of bigotry and its manifestation as “racism,” “sexism,” “transphobia,” and the like.

WHY DOES THIS MATTER?

First, I want to take a second to note why this matters at all. I am a racial minority in the West and I anticipate a good number of my readers and I will have much shared ancestry. The assumption amongst most of my peers in my racial and age cohort is that wokism advances our interests in the United States; surely the best way to achieve material success and security is to constrain American whites by forcing them to acknowledge their privilege and build a broad coalition with other racial categories?

Whatever is the basis for these rationalizations,[*] this analysis is flawed on several levels. First, it grossly misunderstands the default condition of humanity, which is marked by rampant tribalism — the West has been successful in creating a remarkably tolerant world. Second, it is possessed with a defect ubiquitous among progressives — and frankly, this is too often true of evangelical Christians and political “trad[itionalist] Catholics” as well — that humans are blank slates that can be transformed with sufficient coercion and little cost. They are potted plants that will not push back. Not only is this coercion disgusting, but the failure to recognize that spending the next few decades replicating conditions comparable to those present in Yugoslavia and Rwanda by the 1990s cannot end well. I am not anticipating a race war necessarily so much as heightened levels of background violence, and this should particularly concern economically successful minorities;[5],[6] see Amy Chua’s World on Fire and Thomas Sowell’s essay “Is Antisemitism Generic?”.

Racial conflict should be the primary dimension for concern as that is the route through which there is the greatest likelihood of large-scale violence, though the issue of sexual minorities and other dimensions on the intersectional chart are worth keeping in mind as these movements have been bundled together in recent decades and exploded on the scene to overtake existing institutions in stunning speed under the banner of intersectionality.

Yet, in some ways aspects of this attitude have been present for decades. Christopher Lasch in his 1997 book Revolt of the Elites observed:

Black militants encouraged racial polarization and demanded a new politics of “collective grievance and entitlement.” They insisted that black people, as victims of “white racism,” could not be held to the same educational or civic standards as whites. Such standards were themselves racist, having no other purpose than to keep blacks in their place. The white left, which romanticized Afro-American culture as an expressive, sexually liberated way of life free of bourgeois inhibitions, collaborated in this attack on common standards. The civil rights movement originated as an attack on the injustice of double standards; now the idea of a single standard was itself attacked as the crowning example of “institutional racism.” Just how far professional black militants, together with their liberal and left admirers, have retreated from any conception of common standards—even from any residual conception of truth—is illustrated by the Brawley fiasco. When the “rape” of Tawana Brawley, proclaimed by Al Sharpton and Alton Maddox as a typical case of white oppression, was exposed as a hoax, the anthropologist Stanley Diamond argued in the Nation that “it doesn’t matter whether the crime occurred or not.” Even if the incident was staged by “black actors,” it was staged with “skill and controlled hysteria” and described what “actually happens to too many black women.” William Kunstler took the same predictable line: “It makes no difference anymore whether the attack on Tawana really happened. … [It] doesn’t disguise the fact that a lot of young black women are treated the way she said she was treated.” It was to the credit of black militants, Kunstler added, that they “now have an issue with which they can grab the headlines and launch a vigorous attack on the criminal justice system.” It is (or ought to be) a sobering experience to contemplate the effects of a campaign against “racism” that turns increasingly on attempts to manipulate the media—politics as racial theater.[7]

Replace the names and this excerpt would be perfectly at home today. If Wilfred Reilly is correct, then a substantial portion of hate crime accusations today are fabricated.[8] Nonetheless, then as now hate hoaxes are excused for supposedly speaking to something true. Allan Bloom does not sound out of place from today when he wrote in his 1987 book The Closing of the American Mind that “Students now arrive at the university ignorant and cynical about our political heritage, lacking the wherewithal to be either inspired by it or seriously critical of it,”[9] and a reader who did not know Arthur Schlesinger’s The Disuniting of America had been originally published in 1991 could be forgiven for thinking his mentioning that Crispus Attucks was retconned to be recast as a black man[10] was a recent event.

That these trends have existed for decades raises the question: why did this set of related beliefs abruptly enter retreat in the 1990s and only achieve domination after 2014?

HANANIA & CALDWELL

I am not the first person to attempt to figure this out and I will not be the last. In some ways this is a response to Richard Hanania. Over a span of four articles in “Why is Everything Liberal?” and “2016: The Turning Point” as well as “Woke Institutions is Just Civil Rights Law” and “Liberals Read, Conservatives Watch TV” Hanania argues the progressives care more about the use of government to achieve their ends and progressive attitudes on identity groupings have been influenced by Civil Rights Law — the latter entrenched the belief that disparate outcomes necessarily flow directly from discrimination.

Hanania’s claims that progressives today care more about politics corresponds to my intuitions as well as his assertion that American conservatives have a cognitive style that is not conducive to achieving any policy wins. Perhaps in the future I will delve more into that particular point. This article focuses narrowly on attempting to determine where wokism comes from.

The claim that wokism today is largely a function of civil rights legislation is one that was recently popularized by Christopher Caldwell in The Age of Entitlement. While I agree with Caldwell and Hanania that the 1964 Civil Rights Act contributed to the present moment, I believe this is an incomplete analysis. Hanania is right that government policy can lead to changes in public perception and that the fear of being sued for discrimination must have altered the behavior of firms, but it is not obvious that Civil Rights Law has as much of an influence on suburban wine moms and college activists as it does on those doing the hiring.

Laws and institutional constraints matter and it is true people fall in line behind their copartisan elites; a case in point: Republican voters abruptly swung against free trade in the 2016 election cycle due to Trump.[11] Government policies do affect culture and society, and this can be seen in the different attitudes East and West Germans continue to have on religion, Jews, political preferences, optimism, and so forth.[12] On the Korean peninsula the language has diverged widely under the two governments.[13]

Nonetheless I am not convinced this is an adequate explanation. The divergences that occurred in the Germanys and the Koreas happened under authoritarian and totalitarian regimes, respectively. Though South Korea had an authoritarian regime during the Cold War era, the nature of that regime was still very unlike the DPRK. What this means is imposing institutions is not always sufficient to be transformative. Despite the imposition of a Western style constitution, Japanese politics functions very differently from Western politics. The nature of a people matters and affects how institutions operate. In a classic study on the persistence of behavior:

We find that the number of diplomatic parking violations is strongly correlated with existing measures of home country corruption. This finding suggests that cultural or social norms related to corruption are quite persistent: even when stationed thousands of miles away, diplomats behave in a manner highly reminiscent of government officials in the home country. Norms related to corruption are apparently deeply in- grained, and factors other than legal enforcement are important determinants of corruption behavior. Nonetheless, increased legal enforcement is also highly influential: parking violations fell by over 98 percent after enforcement was introduced. New York City is an attractive location to study increased enforcement relative to many less developed countries, where official changes “on the books” may not always translate into greater actual enforcement on the ground.[14]

While some of the difference must come down to a peoples’ willingness to follow the rules — Scandinavian conformism and honesty at traffic-free red lights come to mind[†][15],[16] — there is a difference between simple laws enforcing traffic rules versus the relative open-endedness of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Willingness to follow and enforce existing laws must come from somewhere as well as the willingness to interpret them expansively. Rules in authoritarian regimes are akin to foot binding while rules enforced in liberal democracies are akin to breaking into new shoes.

Important caveat: it is true authoritarian states have some laws that have no social consequences. Consider the 1977 Constitution of the Soviet Union that guaranteed free speech. Ideology confers different levels of importance on different rules and in the USSR the supremacy of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union overrode other stated commitments in the federal constitution. It remains to be seen how energetically social justice aims will be pursued in the coming decades, but since the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the law has not carried the threat of multiple years of imprisonment nor exile for violations. The relatively light touch given the full spectrum of punitive measures a law could carry means something else is a factor, and again worth emphasizing the willingness to interpret that law expansively had to have preceded the law’s culture reshaping scope.

Perhaps the high social trust of mid-twentieth century America made the country more akin to Scandinavia and that generated an inertia that has continued to the present. Should that be the case, then perhaps Americans just conformed more readily to the Civil Rights Act and did not think much about its logical consequences when left unchecked. Maybe, but given the way political correctness surged, receded, and wokism emerged emerged I strongly suspect the mechanism of its spread is not as straightforward as that would imply.

Also worth noting: the United States still bans cannabis. After five decades and a trillion dollars[17] recreational marijuana is now legal in many states and psychedelics and some narcotics are likely next. America’s drug war leads to two conclusions. First: the relatively high social trust of the time period cannot explain why the consequences of the Civil Rights Act have had more permanence than the escalating punitiveness directed towards drug use. Second: liberal democracies lack the depth of control that would permit them to have the same kind of transformative impact that authoritarian states do. Again: ideology prioritizes different rules and authoritarian states are better at imposing their will on the laws they care most about.

Hanania’s insistence that wokeness is just civil rights also cannot explain why courts, even if “fickle,”[18] would side with plaintiffs often enough that it would warrant reorienting existing firms as much as they did. When the norms were different this would require judicial activism by a critical mass of judges to intentionally take a vague law and make it expansive in scope. To further bolster his belief in government’s power to reshape beliefs he argues the “AAPI” and “Hispanic” constructs the government uses are very weak. However, outside of the activist class there continues to be strong differences within Hispanics. Homophily — overlaps in language and appearance — probably explains why they may cluster, but “Hispanic” is still a weak category. The same is true for East Asians. South Asians sometimes mix with East Asians — both are from high-achieving recent immigrant stock — but usually are separate. Government constructs here provide a niche for some minority activists, but these remain highly superficial. Hanania also fails to make a compelling argument why wokism experienced a two-decade recession and exploded in the latter portion of the 2010s. Other factors are in play.

CAPTURING THE ELITE

When starting this section, I strongly recommend reading Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s article “Most Intolerant Wins” here. The most important thing to keep in mind when reading this piece is that small numbers of highly motivated people can steamroll a passive majority.

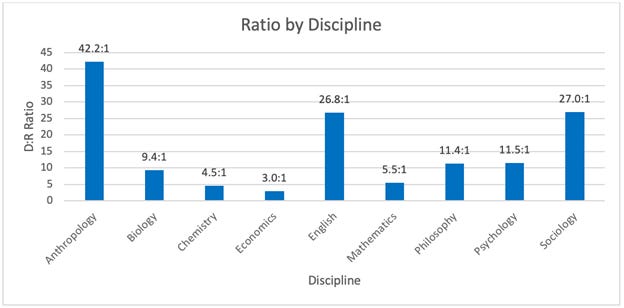

When Jonathan Haidt, Chris Martin, and Nicholas Rosenkranz began Heterodox Academy in 2015, they were pointing out a decades long trend in universities. There probably have always been differences in the partisan affiliations of the people attracted to different jobs,[19] and academia is no different, though the ratios vary widely.[20] This ranges from 3:1 advantage for Democrats over Republicans in economics departments in flagship colleges to 42.2:1 in anthropology.[21]

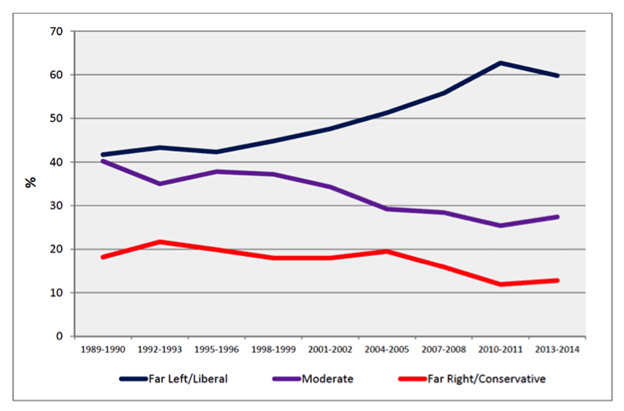

Progressives have long had a numerical advantage, but the size of the gap is a more recent phenomenon.[23]

(While the last chart cuts off at 1989, I welcome information anyone may have on the partisan gaps prior to then.)

As for explaining this gap, I suspect the following happened. Harvard made the SAT compulsory beginning in 1935 and over subsequent decades other universities did so as well.[25] As universities became more academically rigorous and began selecting on the basis of cognitive ability, this selected for a specific range of traits including not just IQ, but interest and other personality factors. Some universities, like those in the University of California system, did not adopt the SAT until 1960.[26] Nonetheless selection on these dimensions should have been the general trend.

It stands to reason those individuals who are higher in the Big Five personality trait of “openness to experience” would be attracted to spending several years in academia and these individuals would be of higher intelligence as well. Intelligence is correlated with openness to experience[27] and the latter is also correlated with progressivism.[28]

Once in these universities, it further stands to reason that those with a comparative advantage in their verbal abilities would then self-select into the humanities. In this milieu these individuals would have been exposed to the neurotic academicians who became trendy, I suspect, largely because of the Second World War. In this same milieu the stars in academia would have been the physicists who were still producing complicated new theories. The standard model was not yet complete, and this was decades before it became apparent theoretical physics had slowed to a near halt.

I bring up physics because I have a nagging suspicion that physics envy played a part. This paragraph is almost entirely speculation on my part as I have asked other people this and not gotten a real answer. What is certain is that activist academicians in this time period used extremely and unnecessarily convoluted sentences in order to sound smart, as noted by Noam Chomsky in this brief clip here.[29] One of my favorite examples of this is quoted in What’s Left by Nick Cohen who excerpted this gem from Judith Butler:

“The move from a structuralist account in which capital is understood to structure social relations in relatively homologous ways to a view of hegemony in which power relations are subject to repetition, convergence, and rearticulation brought the question of temporality into the thinking of structure, and marked a shift from a form of Althusserian theory that takes structural totalities as theoretical objects to one in which the insights into the contingent possibility of structure inaugurate a renewed conception of hegemony as bound up with the contingent sites and strategies of the rearticulation of power.”[30]

As pathetic and transparent as this is, I suspect the desperate need to close the status gap with more serious fields had to have contributed to the rise of reality-bending assertions in the humanities. True, physics had reality-bending claims as well: relativistic physics (though a part of classical mechanics) upended our understanding of spacetime, and the more exotic quantum mechanical claims achieved escape from the outer bounds of human intuition. But physics could be experimentally validated and branches that could not, like string theory, remain strongly contested. Meanwhile the humanities had to offer cultural relativism, reality denial, and a primacy afforded to subjectivity that looks more like intellectual masturbation than any genuine attempt at truth seeking. Add some angsty teenage cool guy cynicism like “nothing is real except power” and there you go.

Later this would become less cynical and incorporate activist elements. For the generation that came of age at this time — the academic currents and the broader world outside, including opposition to the Vietnam War, memories of the Civil Rights Era and the radicalism of the 1960s —would have been exposed to a powerful cocktail of influences and passions in this time of youthful idealism. For young adults, the decade after age fourteen is particularly formative and shows up in an unusual and relatively extreme Democratic lean for individuals born between 1950 and 1954.[31] Even beyond this narrow cohort, it stands to reason a disproportionate portion of young activists may choose to remain at universities where they felt they found their purpose and then shape upcoming young minds. Students self-select and those temperamentally on the left end of the spectrum will be the most likely to adopt these beliefs even if the overall proportion of left-moderate-right students remain unchanged — this produces a small, motivated minority within academia against a passive majority and shifts the Overton window so that self-identification on surveys has limited use in determining how universities shift beliefs.

This did two things. First, it created a positive feedback loop. In the broader job market there already are notable distortions in hiring created by partisan affiliation.[32] A minority political affiliation is less likely to get an individual hired. Imagine the effect when these fields have some with an explicitly activist ethos. It stands to reason that an expressly activist ethos on the part of some academicians, especially when the broader university culture tended towards the pursuit of objectivity (however imperfectly) would mean the partisan skew was to become even more asymmetrical. Second, these activist academicians with their roster of biases increasingly are responsible for determining what passes peer review.

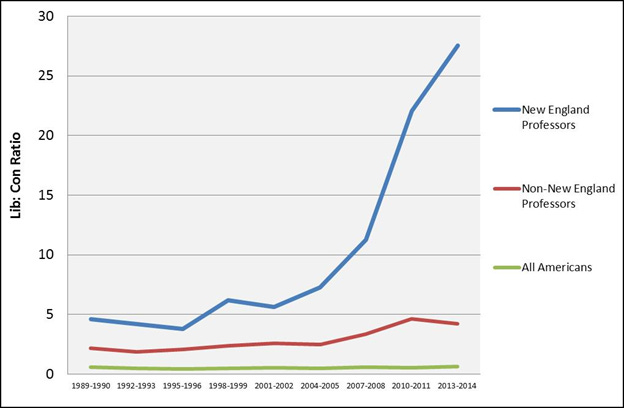

By 2005 individuals born in 1940 started becoming sixty-five. These individuals would have finished high school by 1958, undergraduate studies around 1962, and masters and doctorates in the following few years. The cohort immediately after would have spent more of their formative years in the activist late-1960s. In fact, another analysis that separates partisan skew in the professoriate by geographic region shows an accelerating spike beginning in 2005 in New England:

Given the high concentration of elite universities in New England, this would have an outsized impact on norms transmitted downwards through the rest of academia.

Why is this a problem when the scientific method is to rigorously test the claims made by academicians? First consider the replication crisis. Stuart Ritchie writes his book Science Fictions:

In general, though, the effect on psychology has been devastating. This wasn’t just a case of fluffy, flashy research like priming and power posing being debunked: a great deal of far more ‘serious’ psychological research (like the Stanford Prison Experiment, and much else besides) was also thrown into doubt. And neither was it a matter of digging up some irrelevant antiques and performatively showing that they were bad — like when Pope Stephen VI, in the year 897, exhumed the corpse of one of his predecessors, Pope Formosus, and put it on trial (it was found guilty). The studies that failed to replicate continued to be routinely cited both by scientists and other writers: entire lines of research, and bestselling popular books, were being built on their foundation. ‘Crisis’ seems to be an apt description.”[34]

Estimates on the percentage of replication failures depend on the analysis. Ritchie also writes:

The highest profile of these involved a large consortium of scientists who chose 100 studies from three top psychology journals and tried to replicate them. The results, published in Science in 2015, made bitter reading: in the end, only 39 per cent of the studies were judged to have replicated successfully. Another one of these efforts, in 2018, tried to replicate twenty-one social-science papers that had been published in the world’s top two general science journals, Nature and Science. This time, the replication rate was 62 per cent. Further collaborations that looked at a variety of different kinds of psychological phenomena found rates of 77 per cent, 54 per cent, and 38 per cent. Almost all of the replications, even where successful, found that the original studies had exaggerated the size of their effects. Overall, the replication crisis seems, with a snap of its fingers, to have wiped about half of all psychology research off the map.”[35]

Problems are not confined to psychology — challenges extend to economics, medicine, and other fields with varying degrees of issues around replicability.

Second, consider the Sokal Squared hoax which succeeded in getting Affilia to accept a plagiarized portion of Mein Kampf that had been given a feminist spin[36] and succeeded in landing another piece in Gender, Place and Culture on rape culture and systemic oppression of dogs by gender norms.[37] Why are these papers published?

In Quillette, Lachlann Tierney cites a quote from Richard Spady in the book First Things by Christian Smith. The excerpt goes:

In my experience, when a weak paper with the right message is presented in a faculty of graduate seminar, the attitude is this: This paper has its heart in the right place, and we know [my emphasis] its conclusion is true, so it’ll be OK after a little work on the methodology.[38]

Tierney then argues:

This is a patently backwards process that threatens the very nature of academic inquiry. Academics should be getting the methodology right from the start, basing it in foundational theory and then making conclusions. When the conclusion is a foregone, you in essence have a theological approach to your work. Faith in ideology first, reason second.[39]

Ideological biases worsen distortions. Academia, which has had a leftwing bias for decades, has an unexamined problem where it failed to review findings for validity. Nonetheless some assumptions are hard to kill and they stick around; recall the first excerpt from Science Fictions.

Two conclusions can be drawn from this. The first is that at least this elite corner has had difficulty generating truth claims that can be validated consistently. Academia’s casual relationship with reality and obvious bias, coupled with prestige, makes academia the obvious candidate for the source of the dysfunctional norms peddled by elites. Civil rights and the dysfunction that emerges from the 1964 law really are symptoms of another variable. Second, because academia claims to rigorously test and validate empirical statements, even normal people can buy into its assertions. Normally this would be rational — everyone must outsource knowledge seeking to some degree. For a long time people have vaguely known an ideological bias exists in academia, but who else is vetting knowledge? And if the country is still intact, are these experts really so wrong?

Under normal circumstances the aforementioned conclusions derived would appear to be sensible. All of this is necessary to explain how beliefs confined to some of the ideologically possessed in academia gradually seeped out into broader elite culture.

WORLDWIDE CONSERVATIVE RESURGENCE

When reading Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s The Disuniting of America from 1991, the reader will come across familiar themes. In the years before the collapse of the Soviet Union there had been an upsurge of political correctness. At the time there were already controversies and fights over educating American children on white hegemony, oppression, the sins and iniquities of America’s founders, ethnic conflicts, and the like.[40] While the leftward shift in academia would not become far more extreme until the middle aughts of the new millennium, the undergraduate cohort from around 1968 would come to constitute an increasingly powerful generational tide. As the positive feedback loop selecting for the activist temperament became increasingly powerful, I would wager that by 1990 this academic style probably would have seeped into other fields, though they would not constitute majorities.

Nonetheless, the trend that was called “political correctness” then and “wokism” today did not survive the 1990s in its first iteration. I suspect this was for two reasons.

By the 1980s there was already a broad and worldwide backlash against the left in all angles. Countries from Chile to the United Kingdom, China and the Soviet Union had embarked on programs of market liberalization after noting the success of East Asian countries such as Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. In the United States, Ronald Reagan’s fusionism combining free enterprise with conservative social morality was a powerful response to the excesses of the 1970s, along with a renewed and confident military posture against the Soviet Union.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, it was obvious to the elite that the American liberal tradition had triumphed over leftist coercion. This was an era of Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History — even if the struggle for recognition and technology could mean a reversion, liberal democracy would constitute the final and ultimate form of government. Fukuyama’s following passage from the aforementioned book was telling:

At other times in the past, entire peoples have been written off as culturally unqualified for stable democracy: the Germans and Japanese were said to be hobbled by their authoritarian traditions; Catholicism was held to be an insuperable obstacle to democracy in Spain, Portugal, and any number of Latin American countries, as was Orthodoxy in Greece and Russia. Many of the peoples of Eastern Europe were held to be either incapable of or uninterested in the liberal democratic traditions of Western Europe. As Gorbachev’s perestroika continued without producing any clear-cut reform, many people both inside and outside the Soviet Union said that the Russian people were culturally incapable of sustaining democracy: They had no democratic tradition and no civil society, having been broken to tyranny over the centuries. And yet, democratic institutions emerged in all of these places. In the Soviet Union, the Russian Parliament under Boris Yeltsin functioned as if it were a legislative body of long standing, while an increasingly broad and vigorous civil society began to spring up spontaneously in 1990-1991. The degree to which democratic ideas had taken root among the broader population was made evident in the widespread resistance to the hard-line coup that was attempted in August 1991.[41]

Suddenly the belief that Western liberalism might be inappropriate for some populations was retrograde. Imagine the country after the twelfth year of Reagan-Bush: the collapse of the Berlin Wall, the dissolution of the Soviet Union, and the total victory of the United States of America in the Cold War met victory in Operation Desert Storm — morning in America was accompanied by the end of the Vietnam hangover and the unequivocal validation of the universalism of American liberalism.

In 1984 the Democratic Party ran Walter Mondale and subsequently Michael Dukakis in ’88, both progressives who were soundly routed. But when that party elected Bill Clinton in 1992, the latter consolidated the Reaganite direction of the country by marshaling the support of America’s leftwing party behind welfare reform, punitiveness against crime, and moderation on social policy.

The picture from abroad was mixed; the pendulum swung slightly from the afterglow of Desert Storm in the failed intervention in Somalia, but the next lesson was in favor of intervention again after the fallout of from a lack of intervention in Rwanda, and Yugoslavia validated a muscular projection of American power along with the narrative of promoting Western values. It is scarcely any wonder that the realism of the foreign policy class from Bush ’41 changed, in this milieu, to 21st century neoconservatism under Bush ’43 and confidence in the lead up to the Second Iraq War.

What foreign policy exemplifies here is a generalized return in confidence in America that permeated through foreign, economic, and social policy. The activist left was routed in this decade and the activist trend in this time had a more conservative flavor: consider the pressure for creationism in schools.

Political correctness persisted for a few years into the 1990s though the end date varies based on who you ask. Conservative resurgence worldwide from the 1980s and the events in 1991 first meant the trend had limited currency amongst the elite and the latter set political correctness and affiliated trends into rapid decline; the Ebonics controversy notwithstanding. It is worth repeating that the people who did have proto-wokist tendencies in this time period were already a minority even smaller than today, but their impact on the discourse at least was bound to be large as this was a small activist cohort where everyone was comparatively passive.

Is this a positive sign that the current wokist moment will be short lived? I am not convinced. There may yet be a reversal in the coming years, but wokism has only been accelerating since 2013. It has now gone beyond academia, is far more entrenched in media than in the past, and now appears in corporations and the military. Today the entirety of elite culture is oriented one way and the change has been spectacularly rapid. Recall that in 2017 an American could be forgiven for thinking this would be impossible. An incident like George Floyd was inevitable to happen at some point and the COVID-19 pandemic was an accelerant to a steady and unbending trend.

As for the second reason why the political correctness movement of the 1980s and early 1990s did not succeed was because the adults — middle aged individuals in management roles in government and private industry — would have been socialized prior to the chaos of the late-1960s. A fifty year old in 1990 was born in 1940 and probably would have completed college by 1962 (had he chosen to go). He would be twenty-eight by the raucous year of 1968. This individual, should he be a CEO or in a managerial position of some sort at a firm, might have been pressured to push for diversity initiatives, but these demands would still be relatively alien to his intuitions compared to individuals born in subsequent generations. Unlike any narrow number of activist judges in the late 1960s who could unilaterally create law, a manager or executive in a firm is subject to superiors, boards of directors, and the like. Room to maneuver is limited and conformism is imposed organically; social constraints emerging from the consensus of that generation limited the spread of political correctness.

The current moment is different.

“SCIENCE ADVANCES ONE FUNERAL AT A TIME”

When Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt published The Coddling of the American Mind in September 2018 three years after an article of the same name was published in The Atlantic in 2015, they attempted to identify the causes of the trends on college campuses. Lukianoff and Haidt identify a few trends. The authors point to helicopter parenting as one of the factors. Lukianoff and Haidt argue unstructured free time is essential for children’s development as to allow them to learn from social conflicts with their peers and gain resilience.[42]

Safetyism is another related factor. Almost all cases of missing children are runaways that return home or a child picked up by other family members; Lenore Skenazy in Free Range Kids cites “British author Warwick Cairns, who wrote the book How to Live Dangerously: if you actually wanted your child to be kidnapped and held overnight by a stranger, how long would you have to keep her outside, unattended, for this to be statistically likely to happen? About seven hundred and fifty thousand years.”[‡][43] (Emphasis from Skenazy.) At the same time parental and government intervention in education has very little impact on intelligence[§] as validated through twin studies,[44] genome-wide association studies demonstrate polygenic scores are far better predictors of educational attainment than environmental inputs,[45] and even the quality of educational institutions within a country have next to no impact on lifetime outcomes.[46]

Despite the low risk of abduction for children and the inability of parents — outside of neglect and abuse — to change the academic abilities and lifetime incomes of children by much in modern day America, safetyism and credentialism have become twin drivers that lead parents to shelter their children and this denial of experience creates a more fragile generation with rising rates of mental illness, self-harm, and suicide.[47] Lukianoff and Haidt compare adversities children experience in their social groups such as rejection, teasing, and the like to how exposure to allergens in early childhood prevents the development of allergies.[48] By the time children complete high school and enter college, these individuals with stunted social experiences are much more neurotic than past generations and incapable of handling disagreement and other forms of conflict.[49] They also become politically conscious at a time when high polarization[**] makes everything done by the opposition seem catastrophic and evil,[50] while social media accelerates the speed at which awareness of seemingly apocalyptic events spreads. These dynamics appear in a sudden spike in attempts to shut down campus speakers and occasionally through violent protest. Catastrophizing language surrounding this shows the neuroticism manifests itself in fear of disagreeing speakers and the political polarization exacerbates the perception of danger from the opposition.

An immediate objection is that this phenomenon is not true in all universities, but only a narrow slice of elite colleges. This is true. Note that this is a phenomenon in the upper-middle and upper classes. Lower ranked universities experience this phenomenon to a much lesser degree. As helicopter parenting, safetyism, and credentialism are upper-middle class diseases, these objections do not invalidate the findings by Lukianoff and Haidt. Also true is the fact that large numbers of people still believe free speech is important and polling shows moat people reject wokist assumptions. But that does not matter.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s concept of “antifragility” makes sense of why adverse social experiences in childhood and risk taking is necessary for producing healthy, well-adjusted adults. Here we will return to another concept he popularized: the dictatorship of the small minority.[51] This is not a new concept, but Taleb articulates this uniquely well. In his reckoning about “three or four percent of the total population” is needed to actively and aggressively support an idea for a passive majority to accept it.[52] Consider that one estimate puts “Progressive Activists” at eight percent of the American population.[53]

SJWs HATE THIS, ONE WEIRD TRICK TO GET RID of WOKISM

Early in the twentieth century the selection process for university students shifted to prefer those higher in intelligence and openness to experience.

By the middle portion of the last century, nihilistic relativism was popular in the academy. Opposition to the Vietnam War and socialization into the oikophobia widespread in the humanities in this time socialized a segment of the young generation into an activist ethos. Students with an activist temperament were particularly likely to be selected into academia. Activists would not even need to constitute a majority, but rather a highly motivated minority to create widespread shifts and produce a positive feedback loop that would accelerate the ideological homogenization of certain social sciences.

By the 1980s the activist ethos in the humanities became more pronounced and began to spill into attempts to change education policy. The American public was broadly hostile and the generation of the elite in control were unpersuaded. A backlash against the left was in full swing as Americans corrected for the excesses of the 1970s. The knockout punch was delivered by the collapse of the Soviet Union and discrediting of leftism on social, economic, and foreign policy dimensions. Wokism in the first iteration, political correctness, was most virulent in the humanities and certain assumptions had more currency in elite universities broadly, but the infection was contained.

Around 2014 entered a cohort of students who were distinct in several keyways. This cohort was born several years after the collapse of the Soviet Union. For many of them, September 11th was on the horizon of the earliest memories and had a modest impact compared to the impact the same event had on other living generations. What was more memorable was the election of Barack Obama and the debates around gay marriage. A segment of this cohort was also especially neurotic, exacerbated by the lack of social experience during youth. This small minority was able to shift the discourse and culture in universities. By combining the natural leftward disposition of young people, increased neuroticism in the era of safetyism, and social media it produced the necessary ingredients to create a highly motivated cohort of people eager to impose a narrow and catastrophizing ideology we designate as wokism.

The 22-year-old college graduates from 1991 were 51 by the year 2020. The average age of an American CEO is 54.1 and for a chief financial officer that age is 48.9.[54] The generation that was socialized in college during the first phase of political correctness in universities are now C-suite executives in large firms. Those executives don’t necessarily have to be humanities graduates from an elite university, but acclimated and conversant in the elite discourse around these assumptions. Unlike the 1968 undergraduate humanities generation for whom grievance ideologies were novel and narrowly confined, by 1990 this would have seeped into other disciplines, even if not dominant. I suspect affirmative action outside of activist disciplines, the mismatch effect, and subsequent imposter syndrome would have produced a set of academicians amenable to an activist ethos. Again this would not need to constitute a majority, but an active minority. Consequently the elite undergraduate generation of 1990 would have been far more steeped in these ideas than their parents. People tend to misunderstand the degree to which their peers shift their Overton windows. They may even deride the extremists without realizing just how many of extremists’ beliefs they have adopted.[††] This generation would increasingly be in leadership by 2015, especially at elite levels.

Add a cohort of young neurotic employees entering beginning in 2017, a culture saturated with the narrative of police brutality (even before George Floyd), plus the threat of legal action posed by Civil Rights Law, then the consequences are inevitable. The first aligned the incentives to peoples’ moral intuitions and popular demand, the second defanged the opposition to wokism at a visceral level, the last was already engaged in a long march through the nation’s institutions as conservatives had been pointing out for years. All of this was met by adults in charge who were not exactly allergic to the stuff so the hostility was muted and it was much easier to fall in line. As the activist ethos captured all of the prominent institutions, suburban wine moms, who are women after all, fell in line with the moral consensus.

How do we account for the libertine ethos of the sixties and authoritarian nature of today’s activist left? One plausible explanation is that now that the activist left ethos is in power, there is no incentive to challenge an existing orthodoxy. I certainly believe there is something to his. However, the more important point is that few people have coherent beliefs. Recall the point earlier about how Republican voters flipped on free trade to align better with their standard bearer. Outside of free speech activists and a political class which thinks about speech more often than others, the First Amendment is not something that many thought about until it became a partisan issue for conservatives losing the culture war recently. Strong majorities in the 1990s (up to 63% in 1999) through the aughts supported an amendment to ban the burning of the American flag,[55] and a strong plurality of 49% continued to believe the same at least in 2020.[56] Majorities have never quite been on board with free speech beyond the vague notion that it is good.

But wait — did I not just contradict myself? Not quite. Compared to the antiracist activists, just how powerful are free speech activists? American elites appear to take free speech for granted while antiracism is an urgent national project. One powerful, intransigent minority came into contact with another powerful, intransigent minority and the antiracist one won. The free speech people popular with those who like to think about free speech in the last activist era of the late 1960s have mostly been annihilated.

Another important lesson from the polling numbers: because free speech has a low priority amongst the broader public, it is not as morally laden as it is for other issues. Because few have coherent beliefs, people understand where their copartisan elites are and which direction to point. If few Americans care about free speech, but they think racism is very bad then of course free speech will be subverted in service of some other more important goal. If you knew few details about George Floyd except the video then anyone could be forgiven for believing racism is a very big problem, perhaps even more than speech.

Given the generational nature of this, it is reasonable to ask: does this mean that once people who came of age in the 2000s begin to lead companies and institutions that wokism will be rolled back? This is not so certain because wokism is now too thoroughly entrenched in nearly every major institution from private industry to the military. Partisan commitments and taboos to opposition against wokism will socialize upcoming generations into these assumptions. While Civil Rights Law has been influential, the mechanism has been different: influence has flowed from motivated elites with outsize power to reinterpreting existing rules and norms that ultimately reshape popular behavior.

I may elaborate more on this in the future, but what this article should lead you to conclude is wokism is here to stay for at least a full generation. Children who are born today may rebel against the morality of their parents’ generation, but if so we should not anticipate any rollback in earnest until after 2042, around the same time the white majority becomes a mere plurality, which also raises the probability of balkanization and internecine violence. Opposition to wokism will be futile for the foreseeable future. Even if the Civil Rights Act of 1964 accounted for most or all of what caused wokism, its repeal would be insufficient for the same reason the 1996 passage of Proposition 209 in California failed to permanently eliminate affirmative action. Bureaucrats, busybodies, and true believers will find ways to destroy the opposition; so the best any thinkers can do today is to have well-developed ideas ready if wokism as a consensus breaks down. No ONE WEIRD trick here.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abrams, Sam. 2016. The Blue Shift of the New England Professoriate. July 06. Accessed February 03, 2022. https://heterodoxacademy.org/blog/the-blue-shift-of-the-new-england-professoriate/.

n.d. Average age at hire of CEOs and CFOs in the United States from 2005 to 2018. Accessed February 03, 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1097551/average-age-at-hire-of-ceos-and-cfos-in-the-united-states/.

Bloom, Arthur. 1987. Closing of the American Mind: How Higher Education Has Failed Democracy and Impoverished the Souls of Today's Students. Simon & Schuster.

Booth, Michael. 2015. The Almost Nearly Perfect People: Behind the Myth of the Scandinavian Utopia. Picador.

Carroll, Joseph. 2006. Public Support for Constitutional Amendment on Flag Burning. June 29. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://news.gallup.com/poll/23524/public-support-constitutional-amendment-flag-burning.aspx.

Chua, Amy. 2004. World on Fire: How Exporting Free Market Democracy Breeds Ethnic Hatred and Global Instability. Anchor.

Cohen, Nick. 2007. What's Left? Fourth Estate.

de Neve, Jan-Emmanuel. 2015. "Personality, Childhood Experience, and Political Ideology." Political Psychology 55-73.

deBoer, Fredrik. 2020. The Cult of Smart: How Our Broken Education System Perpetuates Social Injustice. All Points Books.

Fisman, Raymond, and Edward Miguel. 2007. "Corruption, Norms, and Legal Enforcement: Evidence from Diplomatic Parking Tickets." Journal of Political Economy 1020-1048.

Fukuyama, Francis. 2018. The End of History and the Last Man. L. J. Ganser.

Gift, Karen, and Thomas Gift. 2015. "Does Politics Influence Hiring? Evidence from a Randomized Experiment." Polit Behav 653–675.

Goldman, Samuel. 2016. Why Isn’t My Professor Conservative? January 07. Accessed February 03, 2022. https://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/why-isnt-my-professor-conservative/.

Gramlich, John. 2019. How the attitudes of West and East Germans compare, 30 years after fall of Berlin Wall. October 18. Accessed February 03, 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/10/18/how-the-attitudes-of-west-and-east-germans-compare-30-years-after-fall-of-berlin-wall/.

Hanania, Richard. 2021. 2016: The Turning Point. April 28. Accessed February 03, 2022. https://richardhanania.substack.com/p/2016-the-turning-point.

—. 2021. Liberals Read, Conservatives Watch TV. November 01. Accessed February 03, 2022. https://richardhanania.substack.com/p/liberals-read-conservatives-watch.

—. 2021. Why is Everything Liberal? April 21. Accessed February 03, 2022. https://richardhanania.substack.com/p/why-is-everything-liberal.

—. 2021. Woke Institutions is Just Civil Rights Law. June 01. Accessed February 03, 2022. https://richardhanania.substack.com/p/woke-institutions-is-just-civil-rights.

n.d. History of the SAT: A Timeline. Accessed February 03, 2022. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/sats/where/timeline.html.

Jones, Bradley. 2017. Support for free trade agreements rebounds modestly, but wide partisan differences remain. April 25. Accessed February 03, 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/04/25/support-for-free-trade-agreements-rebounds-modestly-but-wide-partisan-differences-remain/.

Jussim, Lee, Jonathan Haidt, and Chris Martin. n.d.

Langbert, Mitchell, and Sean Stevens. 2020. Partisan Registration and Contributions of Faculty in Flagship Colleges. January 17. Accessed February 2022, 2022. https://www.nas.org/blogs/article/partisan-registration-and-contributions-of-faculty-in-flagship-colleges.

Lasch, Christopher. 1996. The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy. W. W. Norton & Company.

Lee, Nathaniel. 2021 . America has spent over a trillion dollars fighting the war on drugs. 50 years later, drug use in the U.S. is climbing again. June 17. Accessed February 03, 2022. https://www.cnbc.com/amp/2021/06/17/the-us-has-spent-over-a-trillion-dollars-fighting-war-on-drugs.html.

Lukianoff, Greg, and Jonathan Haidt. 2018. The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure. Penguin Press.

Mair, Victor. 2014. Is Korean diverging into two languages? November 6. Accessed February 03, 2022. https://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=15534.

Morris, Kathy. 2020. DEMOCRATIC VS. REPUBLICAN JOBS: IS YOUR JOB RED OR BLUE? November 02. Accessed February 03, 2022. https://www.zippia.com/advice/democratic-vs-republican-jobs/.

Mounk, Yascha. 2018. What an Audacious Hoax Reveals About Academia. October 05. Accessed February 03, 2022. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2018/10/new-sokal-hoax/572212/.

mr1001nights. 2011. Chomsky criticizes postmodern feminism & marxism. October 31. Accessed February 03, 2022.

Ngo, Andy. 2018. At this Portland Bakery, White Guilt Poisons the Batter. June 05. Accessed February 03, 2022. https://quillette.com/2018/06/05/portland-bakery-white-guilt-poisons-batter/.

Pinker, Steven. 2002. The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature Hardcover. Viking.

Plomin, Robert. 2019. Blueprint, with a new afterword: How DNA Makes Us Who We Are. The MIT Press.

n.d. Profiles of the Hidden Tribes. Accessed February 03, 2022. https://hiddentribes.us/profiles/.

Reilly, Wilfred. 2019. Hate Crime Hoax: How the Left is Selling a Fake Race War. Regnery Publishing.

Ritchie, Stuart. 2020. Science Fictions: How Fraud, Bias, Negligence, and Hype Undermine the Search for Truth. Metropolitan Books.

Rufo, Christopher. 2021. The Woke-Industrial Complex. May 26. Accessed February 03, 2022. https://www.city-journal.org/lockheed-martins-woke-industrial-complex.

Schlesinger, Arthur Meier. 1998. The Disuniting of America: Reflections on a Multicultural Society. W. W. Norton & Company.

Schretlen, David, Egberdina van der Hulst, Godfrey Pearlson, and Barry Gordon. 2010. "A Neuropsychological Study of Personality: Trait Openness in Relation to Intelligence, Fluency, and Executive Functioning." J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1068-1073.

Shrier, Abigail. 2020. Irreversible Damage: The Transgender Craze Seducing Our Daughters. Regnery Publishing.

Skenazy, Lenore. 2009. Free-Range Kids, Giving Our Children the Freedom We Had Without Going Nuts with Worry. Jossey-Bass.

Sowell, Thomas. 2005. Is Anti-Semitism Generic? July 30. Accessed February 03, 2022. https://www.hoover.org/research/anti-semitism-generic.

Taleb, Nassim Nicholas. 2016. The Most Intolerant Wins: The Dictatorship of the Small Minority. August 14. Accessed February 03, 2022. https://medium.com/incerto/the-most-intolerant-wins-the-dictatorship-of-the-small-minority-3f1f83ce4e15.

Tierney, Lachlann. 2018. The Decline of the Humanities and What To Do About It. August 06. Accessed February 03, 2022. https://quillette.com/2018/08/06/the-decline-of-the-humanities-and-what-to-do-about-it/.

[*] My anecdotal experience is that East and South Asian antiracism is usually often originates from: kindergarteners when I was in kindergarten made fun of my food from home. That happens! I may write more on this in the future, but these ancient resentments are a poor basis for adult morality. I, and you probably too, said incredibly rude things as children.

Also in my experience most white racists from childhood grew up to be pitiable losers. Perhaps that eases things and I feel no compulsion to support destructive and immoral race relations for vindictive reasons.

[†] Michael Booth in his book The Almost Nearly Perfect People contains a few amusing anecdotes of his time in the Nordic countries. He mentions similarities between the Finns and Scandinavians, and one on page 258 of the Kindle edition sticks to mind: “There were audible gasps of disapproval when I crossed the road on a red light, even though there was not a car in sight.” Later in pages 358-359 he provides this:

My rebellious streak has been tamed by the sheer weight of Scandinavian social collectivism, but on this occasion, looking briefly both ways, my head held high, I crossed while the light remained red. An aggressive act in Denmark, I imagined this would be even more provocative in Sweden. A woman to one side of me, who obviously wasn’t concentrating, took my action as a subliminal prompt, and began to cross the road, too, but at the last second she looked up, saw the red light, and hurried back sheepishly on to the pavement. I believe I heard a “tut” from one of the others in the group, but I can’t be sure. Anyway, I made it safely to the other side of the road, turned to the group, and raised my palms in a “See, I survived!” gesture, but they were all still looking up toward the red light in expectant obedience.”

[‡] There are millions of American children, so there will always be real abductions. The important point is that it remains spectacularly rare.

[§] Obvious caveats include malnutrition, abuse, neglect, lack of stimulation, and so forth. Outside of those extremes, genetics appear to play a primary role. The secondary role is played by peer group influences, which is where The Coddling comes into play. Direct parental intervention otherwise – like reading bedtime stories or playing Mozart for the infant – do not appear to have any meaningful effect on cognitive ability. People sometimes argue poverty matters, and I agree it probably does. Especially in developing countries. The problem is “poverty” in America is almost always fake.

[**] This will require a piece all on its own.

[††] Some years ago I participated in a group of College Democrats and College Republicans on a project which was almost certain to fail. The important takeaway from this was meeting university students from the America Northeast in highly ranked universities. More than a few of the complained about “SJWs,” as was the popular term for the woke at the time, and swore up and down that they were moderates. I found some of these same people (mostly) indistinguishable from SJWs and communists. They always seemed to think the troublesome people were just a hair more extreme, and just a hair too far. It does not require identification with living caricatures to have adopted some or a substantial amount of their features.

[1] (Shrier 2020, 97)

[2] (Ngo 2018)

[3] (Shrier 2020, 126)

[4] (Rufo 2021)

[5] (Sowell 2005)

[6] (Chua 2004)

[7] (Lasch 1996, 136-137)

[8] (Reilly 2019)

[9] (Bloom 1987, 56)

[10] (Schlesinger 1998, 66)

[11] (Jones 2017)

[12] (Gramlich 2019)

[13] (Mair 2014)

[14] (Fisman and Miguel 2007, 1045)

[15] (Booth 2015, 258)

[16] (Booth 2015, 358-359)

[17] (Lee 2021 )

[18] (Hanania, Woke Institutions is Just Civil Rights Law 2021)

[19] (Morris 2020)

[20] (Langbert and Stevens 2020)

[21] (Langbert and Stevens 2020)

[22] (Langbert and Stevens 2020)

[23] (Goldman 2016)

[24] (Jussim, Haidt and Martin n.d.)

[25] (History of the SAT: A Timeline n.d.)

[26] (History of the SAT: A Timeline n.d.)

[27] (Schretlen, et al. 2010)

[28] (de Neve 2015)

[29] (mr1001nights 2011)

[30] (Cohen 2007, 54)

[31] (Lukianoff and Haidt 2018, 213)

[32] (Gift and Gift 2015)

[33] (Abrams 2016)

[34] (Ritchie 2020, 32)

[35] (Ritchie 2020, 31)

[36] (Mounk 2018)

[37] (Mounk 2018)

[38] (Tierney 2018)

[39] (Tierney 2018)

[40] The Disuniting of America

[41] (Fukuyama 2018)

[42] (Lukianoff and Haidt 2018)

[43] (Skenazy 2009, 16-17)

[44] (Pinker 2002, 379)

[45] (Plomin 2019, 156)

[46] (deBoer 2020, 108)

[47] (Lukianoff and Haidt 2018)

[48] (Lukianoff and Haidt 2018)

[49] (Lukianoff and Haidt 2018)

[50] (Lukianoff and Haidt 2018)

[51] (Taleb 2016)

[52] (Taleb 2016)

[53] (Profiles of the Hidden Tribes n.d.)

[54] (Average age at hire of CEOs and CFOs in the United States from 2005 to 2018 n.d.)

[55] (Carroll 2006)

[56] (Ballard 2020)